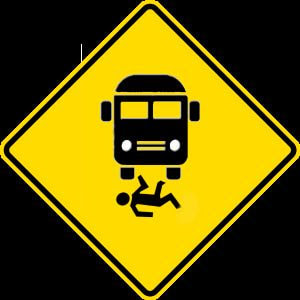

Yet every year brings a new local government case study of how not to deliver services. Last year the poster child was Wellington City Council’s Island Bay cycleway. I was wondering how that community engagement disaster could ever be beaten. That is until this year’s public transport reforms led by the Greater Wellington Regional Council rolled along. “Train wreck” is probably not too harsh a summary of what ensued.

I believe that the most important, if not the only thing of real value possessed by an organisation or individual is their reputation.

That said, very few if any organisations have key performance indicators for reputation. It’s something that is never formally on their radar and something they do not devote any real resources to protecting or enhancing in a measurable way. Perhaps this explains why it gets treated with contempt.

In the past few months, the Greater Wellington Regional Council has enjoyed reputation meltdown of epic proportions. It has gone from being “that forgotten council”, community newspaper fodder where retired mayors and Members of Parliament could quietly supplement their National Super, to one that is front-of-mind for most of the region’s residents, being particularly distrusted and loathed by the region’s public transport users.

Does that outcome seem to worry that Council? Surprisingly, no, if its strategy of denial and blame-shifting is any indicator.

So what went wrong with Wellington’s public transport network in July 2018?

- A solution was provided to something that most community members didn’t see was a problem. Wellingtonians were largely happy with their bus network, widely regarded as New Zealand’s best, and were unaware that it was “on the brink of failure” until a Regional Council manager made that surprising revelation.

- The council’s “solution” was ideological and not based on any meaningful community engagement. The council’s policy analysts have an unshakeable belief in what they refer to as a “north south topology”. They believe that success will come from combining this with an atomic clock and punitive fines for operator non-compliance.

- Community engagement, such as it was, overlooked many community groups with an active interest in or use of public transport services. The council made no effort to go after hard-to-reach groups who are active users of public transport, such as young families, school kids, beneficiaries, aged people, recent immigrants and people with disabilities. Even peak-time commuters seem to have been overlooked, if comments at recent public meetings and online are any indicator.

- An unstated objective was to reduce costs, rather than enhance services. This is backed by the council’s desire to blame the previous government’s Public Transport Operating Model (PTOM) as the reason it chased low-ball tenders. PTOM contains no such requirement.

- The Regional Council over-promised and then massively under-delivered the changes. Large portions of supporting infrastructure were uncompleted, services such as Real Time Information were completely untested and failed spectacularly, and council management has admitted that passenger load testing was not part of their planning. Indeed over 15 years of “big data” available from Snapper went unused because the council did not want to pay for it.

- Most of the service delivery business was let to a bus operating company with no experience, no systems or infrastructure, no buses, no drivers and no money. The Regional Council has invested many millions of dollars to ensure that this company succeeds. This company is also strongly anti-union, which aligns nicely with the council’s desire to lower wage costs.

- Any scope for flexibility, adjustments or rapid changes was foregone for pedantically detailed contracts with service providers. This makes it really hard for council to quickly introduce new or extend existing services.

In simple terms, what was unveiled at a cost of many tens of millions of ratepayer-funded dollars just doesn’t work. More galling is a reluctance from Regional Councillors and their officers to admit blame or to seek solutions to fix the train wreck they have created. They have grudgingly made themselves available to attend public protest meeting organised by local MPs and others. They have promised an independent review, when a rear-view mirror is the last thing that’s needed. They are doggedly determined to make their new system work, yet they have no basis to believe that, given unlimited time, money and community patience, it ever will. Meanwhile they have lost their Social License to Operate.

A social license to operate, or SLO, is a term used to describe the level of acceptance or approval by local communities and stakeholders of organisations and their operations. In simple terms, it’s reputation by a different name.

Some organisations value it highly, and invest heavily in maintaining strong relationships with stakeholders, communities of interest and the general public. Other organisations, particularly characterised by New Zealand local government councils, care not a jot for their organisation’s external reputation. Part of their terms of engagement with communities is to only do what legislation requires of them, and to seek any opportunity possible to avoid it. They only engage when a law says they have to, rather than because they want to and would be hard pressed to argue otherwise.

Over several years the Regional Council has been building a brand – Metlink – for its public transport services. What Metlink’s brand values are supposed to be is a mystery. They clearly don’t include attributes such as honesty, trust, reliability or transparency. On recent efforts it’s clear they do include such traits as inconveniencing the travelling public, bullying and obfuscation – not what a business seeking to create a “zesty green region” should be seeking to attain.

The Metlink brand has become a smelly turd. While the Regional Council may try to roll it in glitter and add V I Poo™ to its container, it will remain a smelly turd. It will always be remembered as such, even in the unlikely event that in the future the public transport network it represents can be made to work. A competent professional marketer would probably advise rebranding once the old Metlink has been flushed away.

Solutions?

Honesty and openness from the Regional Council would work well. One of the key principles of effective community engagement is knowing that if you treat people as adults, they will respond as adults.

Another key principle is to share a problem with a community and to ask for solutions. It is well known, amongst community engagement professionals at least, that a crowd will always produce a better solution than will an “expert”.

Rather than calling for written submissions and organising a few public meetings, Councillors and officers need to actively seek community engagement, particularly with groups that are hard to reach, like the young and the old, infirmed, non-English speaking, working-class heroes that use public transport yet have neither the time nor the ability to cope with constructing a written submission or giving up watching a more accessible train wreck such as Married At First Sight to get to a meeting in a school hall.

Local government only ever does community engagement because it has to, not because it wants to. Regrettably changing that mindset will not happen quickly, or indeed at all, unless train wrecks become more commonplace.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed